NTS: KMRU - Joseph Kamaru Special

“A career-spanning retrospective of KMRU's grandad, the King of Kikuyu Benga. Joseph Kamaru, 'Heavy Combination 1966 - 2007' runs through the Kenyan icon's varied archive, expanding the story with detailed essays and photos from the family vault— Boomkat

Joseph Kamaru - ‘HEAVY COMBINATION 1966-2007’ Listening events

Berlin - 29th October

London - 12th November

Nairobi - TBA!!!

JOSEPH KAMARU

Heavy Combination 1966 - 2007

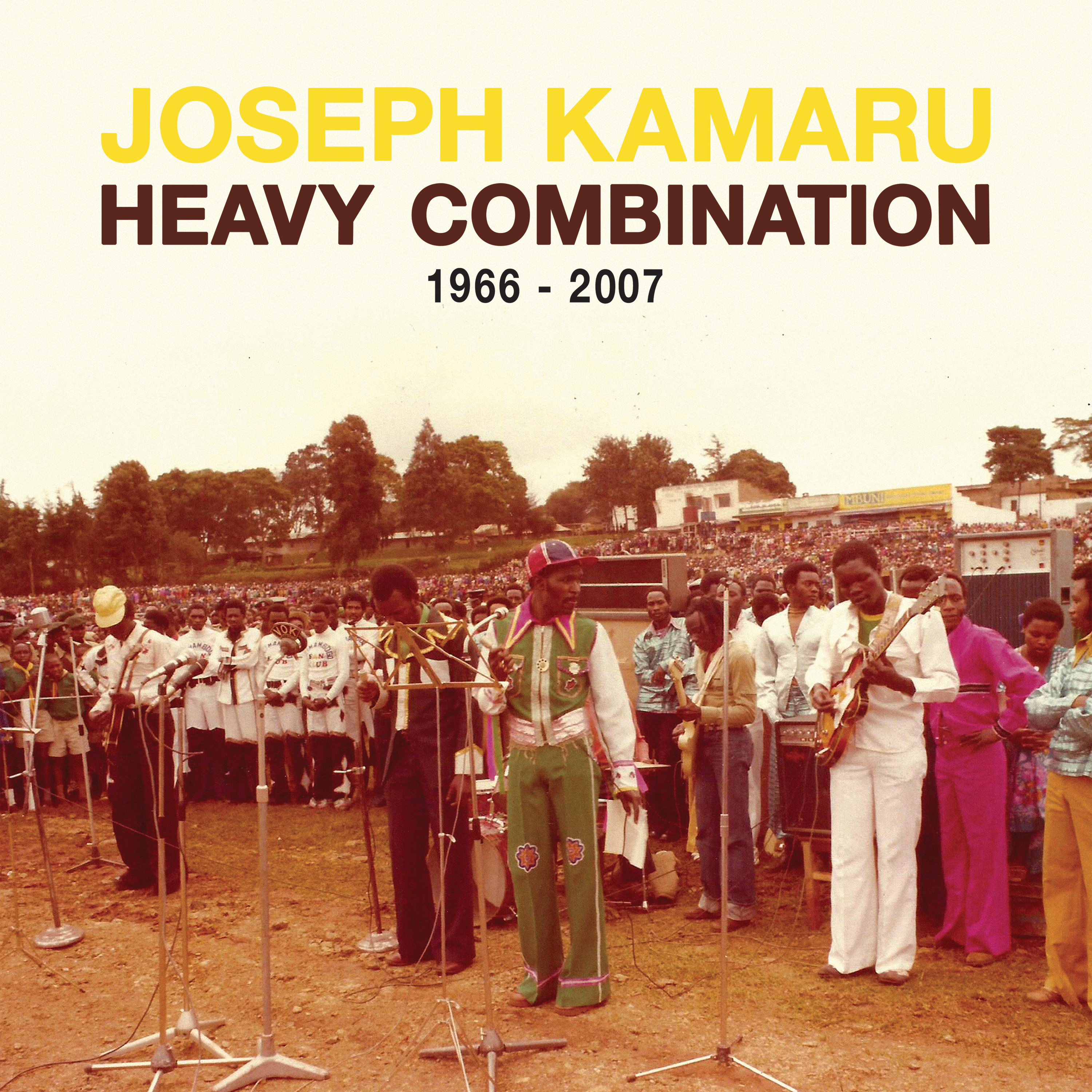

A crucial introduction to the 'King of Kikuyu Benga' and the first career-spanning retrospective of the incredible catalogue of the late, great Joseph Kamaru.

17 tracks that run the gamut from vibrant dancefloor chants with high life-esque guitars, to afro funk, drum machine and keyboard driven disco grooves, and folk style laments. The music is raw, immediate, danceable, and packed full of memorable hooks. The incisive lyrics range from protest songs to relationship advice. Joseph Kamaru was an incredibly popular figure in his native Kenya, connecting with everyone from high-powered politicians to the rural and urban working class, and his music deserves a much wider international audience.

Compiled in partnership with Joseph Kamaru's grandson, the sound artist KMRU.

The tracks have been carefully remastered from original tape transfers by Dubplates & Mastering in Berlin.

Sleeve designed by Karolina Kołodziej using original archive material from the Kamaru family vaults.

Extensive liner notes include essays by Kenyan academic Maina wa Mũtonya, music journalist Megan Iacobini de Fazio, and KMRU himself.

-

“A career retrospective of Kenyan benga music pioneer Joseph Kamaru is released. Co-curated by his grandson, the sound artist KMRU, Heavy Combination (Disciples) showcases Kamaru’s infectious blend of 70s funk with plaintive group vocals, highlife guitar and driving grooves. An east African gem.” - The Guardian

-

Cashmere Guest Mixes Weaving a Rainbow w/ KMRU & Chef Kabui

In this one-off show KMRU and Chef Kabui meet for the first time. Though belonging to different generations, both grew up in the same parts of Nairobi with relatives in Murang’a county. The title of the show “Weaving a Rainbow” refers to an essay (https://www.chefkabui.com/blog-1) Kabui wrote in 2022 about KMRU’s grandfather, the famous Kenyan benga musician Joseph Kamaru. Four years earlier the artist died, —or, to use the Gĩkũyũ phrasing, “fell asleep”. Alongside creating his own music, KMRU has since archived and re-issued the music of his grandfather (https://josephkamaru.bandcamp.com), or of “guka” (Gĩkũyũ for “my grandfather”) as he refers to him. For Kabui, as for many other Kenyans, Joseph Kamaru is an incredibly important figure, he explains in his story, “there was almost no moment of significance in my life that Kamaru was not present as the theme music.” Kabui then recounts how he met him one day in 1986 when he still attended secondary school. Earlier in the day he had heard Kamaru’s new hit “Ngita Yakwa” on a jukebox and later on, after an introduction made by his father, they were going in the same car to a concert in his home village. Almost four decades after the encounter, Kabui connects with KMRU to discuss the musician, Gĩkũyũ culture and Kenyan politics. Framed by a superb selection of Kamaru’s songs, they cover different topics, including Kabui’s “Rutere Manifesto”. Inspired by “Russian” kale growing in his backyard, Kabui pushes back against a conventional reading of Karl Marx by drawing on Gĩkũyũ ideas of land and community. He firmly believes that progressive solutions to contemporary challenges can be found by drawing on indigenous practices. “Weaving a Rainbow” is thus not only a short story that reflects on Joseph Kamaru’s influence on Kabui’s life but it also symbolises an intergenerational conversation and the utilisation of different layers of time and culture.

PLAYLIST

Joseph Kamaru – Ngita yakwa

Joseph Kamaru – Ni kirume

Joseph Kamaru – Hurira tindo

Joseph Kamaru – Mbooco iri mbuca

Joseph Kamaru – Gari la trela

Kamaru Celina Band – Kenya Kurungara

Joseph Kamaru – No ithui twari kuo

-

KMRU – composer, musician, archivist

KMRU & Real Vinyl Guru Interview]

..33:08”

A tale of two Kamarus

Two musicians bore the name, Joseph Kamaru, a grandfather lost to time and a grandson in the midst of his destiny. Here’s the story of the Kenyan folk titan and his ambient composer grandson, what they share and the weight of legacy. Interview.

-

This is a tale of two Joseph Kamarus. One a giant of Kenyan folk, history, and politics; outspoken and festive, energetic and upfront. The other, an ambient electronic pioneer; reserved and delicate, modest and thoughtful. The two are bound by name and blood, but separated by a generation, a separation which has brought nuance to each’s sensibility, relationship to the world and use of technology. While Joseph senior worked in Kikuyu proverbs and played from the pulpit of political campaigns, KMRU (Joseph the younger’s moniker, which we’ll use for simplicity sake) is deft in the ways of digital audio workstations and sound samples, making quiet headway as a student in Berlin and Ableton workshop teacher in Nairobi. -

Despite differences, the silent hand of destiny joins the two together, each a different octave on the same musical staff. There was an “inherent connection,” KMRU recounts, “and I think it’s because I was directly named after him.” We spoke with KMRU about his relationship with his late grandfather, trying to find the similarities in the vast differences including how KMRU thinks of his grandfather’s legacy as he works to reissue his music to the world.

Gucokia rui mukaro (returning the river back to its course)

“When I was in high school and maybe in primary school when I would mention the name Kamaru people would ask if I was related to ‘the Kamaru’.” KMRU explains via a Zoom call from his student housing in Berlin. “I didn’t know he was a musician or a famous person. I just knew him as my grandfather. It made me realize that my grandfather was somebody who was important and I should consider talking to him more and getting to know more of his work.”

“The” Joseph Kamaru, who passed away in 2018, was Kenya’s best known folk singer. Combining Benga, jazz, and Congolese Soukous music with Kikuyu (one of Kenya’s largest ethnic groups) proverbs, Joseph Kamaru wrote songs that cut through the political elite and mounted a broad social commentary for a post-colonial Kenya. Growing up in a working class family, Kamaru first entered the public zeitgeist with his 1966 single “Darling ya mwarimu”, telling the story of a young girl who was sexually abused by her teacher. After the song’s release, the Kenyan National Union of Teachers (KNUT) called a nationwide strike, sparking parliamentary debate and necessitating the intervention of then President Kenyatta.

Kamaru’s polemic beginnings continued on for years, attacking taboo subjects like corruption, rape, and later in life, God. “Tiga Kuhenia Igoti” (Don’t Lie to the Court), another landmark track from Kamaru’s vast catalog of over 2,000 songs, condemns a man on trial for rape by embodying the voice of the victim. Then there’s “J.M. Kariuki,” which turned Kamaru’s presidential ally and friend into a political pariah. The song was written when a former Mau Mau detainee and a popular member of parliament, Josiah Mwangi Kariuki, popularly known as JM was found murdered in Ngong Forest with his body mutilated. “J.M. Kariuki” not only describes the grisly murder, but also asks the government to provide the answers to the death of an innocent man (KMRU). Or his outburst during the 1992 Madaraka Day celebrations when Joseph took the microphone in front of a stadium of people to address then President Moi directly, “Don’t sit comfortably with your fimbo (club). I know there are people telling you that you are popular, but the truth is that people do not like you.”

Joseph the senior was not only a maverick for his bold discourse, but for his knack of combining Benga music on guitar with the Congolese finger-style, and the folky swag of his American analog Jim Reeves. The songs are at moments funky, at others meandering, and at all times totally original. Joseph Kamaru’s contagious intermingling of sound has made his work ripe for a new age of artists sampling his music into new genres and mixing it into DJ sets. “There’s this one, I think it was one of the most played songs I have of my grandfather, it’s called ‘Mukukaranake’,” KMRU recalls, “I heard it being played in a festival context in Nairobi where it was blended with ‘This is America’ (Childish Gambino). There were these two DJs playing, and this is also the track that has been used in the Nike ad. It’s a more up-beat funk type of music. I think it was from his first record.”

Ageni eri na karirui kao (two guests love a different song)

Speaking with KMRU one has a wholly different impression. From behind the screen one finds the portrait of a young artist, contemplative and graceful, kind and touchingly introverted. It’s not the figure you’d imagine haranguing a president in front of thousands of spectators or jumping onto tables during wild jam sessions (as Joseph the senior was known to do in his legendary 1950s Nairobi years).

Instead it seems KMRU has a preference for listening. The young artist’s catalog is a collage of sound samples collected with headphone mics and field recorders, reworked and stretched out into an emotive haze. One of KMRU’s breakthrough earlier works was composed during his trip on the East African Soul Train, an artistic incubator along thousands of miles of train lines. Here, KMRU diverged from his tropical house and techno beginnings, deferring to the musical clamouring of the train itself.

Since, KMRU has been a prolific recorder and producer with little regard for traditional notions of structure or glib ideas of attention span. Dabbling in 12 minute tracks and distorted sound, KMRU’s music now proudly bears the experimental essence of ambient and works in the realm of DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations). A stark difference from his grandfather, as KMRU notes, “I think he was a purist in musicianship and he was a tactile musician playing hardware, live guitar and singing.”

While KMRU enjoyed playing guitar with his grandfather, on his debut album OPAQUER, released in 2020, there is almost no identifiable hardware (aside from the piano strung opener) as the soundscapes take shape and evaporate like a passing mist. PEEL and JAR, also both released in 2020, abstract this process even further. For melody, one must fill in the gaps, and any attempt to conjure images is like grabbing-on to flowing water (with a few exceptions).

If KMRU is carrying the musical torch for the family, it is a new flint that feeds the fire. “We had a really close relationship.” KMRU explains, “I’m the only grandson that decided to take up music.” Though the way Joseph Kamaru and KMRU express themselves musically is passing through a long stretch of time and technology, preference and demeanour.

Ambient proverbs and brave dissidence

What remains then of Joseph Kamaru by way of his grandson? Both are prolific in their own right. “My grandfather was always asking me, ‘Have you made something new today?’” KMRU says laughing. There is also the project of restoration and re-release KMRU has undertaken (a daunting task considering the mass of music) which one can support through purchases on Bandcamp. Yet there are subtler elements transmitted, shapeless bonds of heritage that work into the keynotes of the Kamaru name.

One is the art of listening. KMRU spoke of a place on his grandfather’s porch where people were welcome to come and wax out their woes. “He had a bench outside his door where people would come and he would just give advice. Not particularly in music but just life advice for people,” KMRU explains, “When we were having conversations you could hear him pausing and letting time for someone else to speak. Or being engaged like an audience or a crowd and letting people speak and listen.”

Another is a reverence for nature, as a source of inspiration, and at times, sound objects to be placed into the music itself. “He always wanted to be in nature. And he also mentioned to me that he wanted to build a studio outside. I didn’t know what he meant. He wanted the ambience of the spaces to be present when he was making music and not like enclosed rooms. I think it wasn’t until recently, with this reissue project, but when I’m listening to his music I realized he was also aware of the surroundings.” KMRU explains, “I don’t know if it was intentional, using bird sounds or aircraft sounds in his piece. There’s one track where he’s traveling to Japan, “Safari Japan” and at the beginning of the track you can hear the plane taking off. The more I became aware of field recording and this practice of sound, I really wanted to ask my grandfather these questions like, ‘Were you really thinking about the sound aspect?’ or, ‘What was your idea of sound in music?’’”

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, is anchoring in authenticity. “He was the most honest person with his work,” KMRU says of his grandfather. “It’s a difficult task for artists to be very vulnerable and put themselves in weird situations. For my grandfather it was a bit extreme because he was telling these stories where he had to hide himself from the government because he was exposing so much stuff that was happening politically that may have even led him to be killed, but he wanted to share what’s happening, mostly after colonization. From the 60’s and 70’s there’s lots of assassinations happening with members of parliament who wanted to take over or were liked by most of the people in Kenya.” For Joseph Kamaru, truth was power.

“I remember when I started making music I was all over the place, maybe trying to find myself,” KMRU explains of his own path. “Before I was making ambient and texture based music, when I was DJing, I wasn’t sure people would relate or understand and in Nairobi people have this energy or urge to dance. I was battling with myself. Do I really want to be playing House music or just express what I’m really enjoying making at home? In 2019 is when I fully decided I’m just going to do this and see how it goes and just be free and not think so much about what people would say, just expressing myself and being honest with what I want to say with my music. It’s not in context with my grandfather exposing so much happening in social contexts but also his music was just very free.”

The fragile totem of legacy

“My grandfather’s work has been so special and also close to heart and I think very fragile.” KMRU explains. “That’s why I started to think about the reissue project which has been ongoing for two years now.”

So far KMRU has released a scattershot of singles in a semi-chronology on Bandcamp and, more recently, a full album, Kimiiri available on all DSPs. It’s not hard to imagine KMRU sitting on the floor with a spread of archives displayed before him, piecing together his grandfather’s work with the delicate care he gives his compositions. There are albums, eras, styles and greatest hits to sift through and compile, to catalog and consume.

“The last conversations I was having with my grandfather was about his music and what would happen after he’s gone. I think he knew, but he was telling me that he made so much effort to see me and there’s this huge bond that we had together and this project was an impetus. After, we were to work on a project together in the studio.”

Unfortunately the studio collaboration never came to pass. Joseph Kamaru passed away on October 3rd, 2018, and his grandson was left to pick up the pieces of his legacy. “One thing my grandfather told me,” KMRU concludes, “was to protect the name Kamaru. It’s important.” KMRU continues to protect the name, bringing it a new dimension and sense of pride far beyond Kenya for both himself and his grandfather.

RIP Joseph, play on Kamaru.

The Powerful, Political Music of Joseph Kamaru, Kenya’s King of Kikuyu Benga.

By Megan Iacobini de Fazio · February 27, 2020

Joseph Kamaru was only a teenager when he moved to Nairobi from rural Kenya in the late 1950’s, with a dream of one day becoming a musician. A quickly evolving city still a decade away from independence, Nairobi attracted musicians from all over East and Central Africa, and the sounds of Benga, jazz, Congolese Soukous, and Gospel could be heard blasting out from clubs and open windows.

Kamaru made money working as a street-hawker, a house-help, and a fruit seller, saving enough money to buy his first guitar. Within a few years, he’d added the accordion, keyboard, and traditional karing’aring’a and wandindi instruments to his repertoire. By 1965, two years after obtaining freedom from Britain’s colonial rule, Nairobi had become the region’s musical hub, home to countless independent music labels, recording studios, and even the region’s first legal vinyl pressing plant. Competition was tough, but Kamaru’s unique sound, which merged traditional Kikuyu melodies with the distinctive bass guitar riffs and high-pitched vocals of benga, quickly became popular among the city’s revelers.

Amid Kenya’s optimistic yet complex post-colonial years, it was Kamaru’s sobering themes that set him apart. Expressing himself through ambiguous metaphors and Kikuyu proverbs, the young musician sang about sexual harassment, morality, love, and—most strikingly—about politics. Over the next four decades, Kamaru would aim both high praise and bitter criticism at the country’s ruling elite, a habit that resulted in him falling in and out of favor with different Kenyan presidents; Kamaru was both a powerful ally and an enemy to be feared.

“He grew up during the Mau Mau rebellion [the uprising against British colonial oppression], so with so much political stuff happening, it really affected how he wrote his songs,” says Kamaru’s grandson, himself a successful producer and field and sound artist who goes by the name KMRU. After his grandfather’s death in 2018, it was KMRU who decided to reissue his work via Bandcamp, with the aim of using the profits to one day repress the music on vinyl.

Kamaru’s songs often touched upon issues that were considered taboo at the time, treating them with surprising sensibility and nuance. In “Tiga Kuhenia Igoti (Don’t lie to the court),” he tells the story of a young woman who bravely faces her attacker in court: “When we got to your house you tricked me and told me you’ll take me to work tomorrow / At 9pm, I won’t be shamed by men to say that you touched and strangled me,” sings Kamaru, duetting with his sister Catherine. “Lets stop lying to the court, Young man.”

“Having been raised under colonialism and experiencing all those struggles, he felt that it was right for him to use his music to tell stories that really connected with people,” says KMRU.

He once caused outrage with his song “Ndari Ya Mwarimu,” in which he plays the part of a young student who rebukes the advances of a male teacher. In the song, the girl criticizes the Kenyan education system, saying it tolerates sexual harassment, and demands that the teacher be tried by a court of elders. Kenya’s teacher’s union was so enraged by Kamaru’s lyrics that they threatened a nationwide strike, forcing parliament to debate the issue, and President Jomo Kenyatta to intervene and calm the situation.

Kenyatta, who ruled Kenya from independence in 1963 until his death in 1978, understood that having Kamaru in his corner was a powerful asset. But while the musician was happy to lend his support, he wasn’t willing to compromise his principles. “During political campaigns, politicians wanted him to write songs for them,” says KMRU. “He had close relationships with them, but he would also sometimes turn against them.”

By 1969, Kamaru’s musical career was in full swing, but the country around him was in chaos. The country was preparing to hold its first general elections since declaring independence in 1963, but Kenya People’s Union—the only opposition party—was banned, and its leaders arrested. Ethnic tensions flared, and the shooting of popular politician and independence activist Tom Mboya—widely believed to be a politically-motivated assassination—sparked rioting across the country. Kamaru stood by the president, praising him and vehemently criticizing his detractors in the song “Arooma Ka.”

That all changed in 1975, when the body of former Mau Mau fighter and popular politician J.M. Kariuki, was found on top of an anthill in Nairobi’s Ngong Forest, where it’d been burned and brutally discarded. All fingers pointed to Kenyatta’s government: after all, Kariuki had rallied against corruption and criticized the elites in a time when dissent was not tolerated. Despite his close friendship with the president, though, Kamaru refused to stay silent. That same year, he responded with “J.M. Kariuki,” a protest song demanding answers from the government and wishing terrible fate upon the murderers. The incendiary track ended up being an unprecedented hit, selling 75,000 copies within the first week.

“During that time that he had this red beat-up car,” says KMRU, “and lots of people knew it was his car, so he had to hide it, because the government was after him.”

When Kenyatta died in 1978, his successor Daniel arap Moi realized that it was better to have Kamaru as an ally than an enemy, so he invited him on a presidential visit to Japan. The musician wrote “Safari ya Japan (a trip to Japan),” in praise of the president, and would pen several other compositions in his honor.

But like Kenyatta before him, it wasn’t long before Moi learned that Kamaru was as quick to condemn as a he was to offer praise. In 1983, when President Moi launched increasingly repressive measures in an attempt to consolidate his power, Kamaru used ambiguous language and Kikuyu idioms to send the president a warning: “If the bees come out of the hive / Somebody will get stung,” he sang on “Ni Maitho Tunite.”

Kamaru kept churning out songs that demanded justice and fairness, whether in politics or personal relationships, until he converted to Christianity in the 1990’s and swapped political songs for gospel. Still, his influence never dimmed, and politicians were keen to keep him on their side right up until the day he died.

“In his last days, he used to come to my mum’s house and talk to me a lot about music, about life,” says KMRU. Kamaru was proud of his grandson for choosing to pursue music, and for making something so unique. Sound-wise, there is little of Kamaru’s Kikuyu benga in KMRU’s experimental electronica, but his impact has arguably been even deeper: “He told me to stay authentic with the music I do, to stay honest with myself,” KMRU says. “And that’s what helped me, in certain moments, to choose my own path.”

LITERARY MEANING IN JOSEPH KAMARU'S SONGS

By Kanyi Thiong’o

Different scholars of Literature have in the past researched on the literary meanings in Kenya’s popular songs where some of these works have been published in local dailies, in international Academic Journals and some have even have been submitted for the award of Masters and PhD in Literature in different local and international Universities. Some of these scholars include, Kariuki Gakuo, Pauline Mahugu, Maina wa Mutonya, Joyce Nyairo, Kariuki Kiura, David Rotich, Kangangi Wanja, Earnest Monte and Kanyi Thiongo, to mention a few. These studies can be treated as confirmation that literary criticism of the literature that is encompassed in songs as critical reflections of society has defined its space in the media and in the academia.

This article revisits literary meanings conveyed in Joseph Kamaru’s songs to reread history, education and entertainment that is permeated in his songs as discourses of literature. Like all committed artistes Joseph Kamaru has a music career that dates back to the precolonial era the political climate of the dictatorship of the first and the second regimes from the 70’s to the era of multiparty democracy, political songs, love songs, religious songs to mention a few of the thematic areas that have defined his music. Joseph Kamaru does not sing for singing sake. Each of Joseph Kamaru’s songs educates, entertains and informs. These are the three main pillars which every credible work of Literature must achieve.

Joseph Kamaru has a music career that dates back to the 60’s. As Craig Harris observes in Joseph Kamaru Artistic biography, Kamaru has been influencing the music scene since 1967. Influence in this case can be taken to mean, how most musicians in Kenya compose and write their songs. This can be cited not only in the melodic structure, (tune) which marks most of the song. Kamaru’s songs have been studied at master’s level and PhD level. This is evidenced in Kariuki Gakuo’s Master’s thesis A Study of Alienation in Joseph Kamaru’s songs and Ernest Monte PhD on the Songs of the Mau Mau Stellenbosch University to mention but two.

The educative value in Joseph Kamaru’s songs has in the past attracted several levels of attention from various schools of thoughts and disciplines. Literature, Music, Historian, Anthropologists, Sociologists, and even political science scholars have all identified various shades of meanings in Joseph Kamaru’s songs. He Poetic richness, one finds in Kamaru’s songs, the artistic creativity he employs to defamiliarise meaning serves to document Kenya’s history by archiving the experiences that have defined Kenya’s memories from the days of Mau Mau arms struggle to liberate Kenya from colonial hegemony, to political atrocities that Kenya faced during the tabulent times of Jomo Kenyatta’s dictatorship, the ups and downs that Kenya faced under former president Moi and to political and religious practices that define our Nation today.

When Joseph Kamaru released a song on the death of Kariuki J. M. it almost put him in direct conflict with the government of the day. Kamaru through the melodic structure that defines his music, the heartrending lyrics from a literary perspective has succeeded in documenting not just our history but literary and artistic practices that define Kenya’s musical aesthetics as philosophical practices. This will be of essence to the current generation as well as to future generations which will want to peer into the development of Kenya’s literary, musical, and Political ideologies. Kamaru can therefore be thought of as a committed artist as well as a detailed historicist who has used music to see the past and the effect it has had on the present and to prophesy the future. In this context Kamaru has not only reports on what is happening around him but in addition offers sharp criticism on sensitive issues that affect our society. In this view Kamaru qualifies as a New Historicism critic. As Malpas observes historicist criticism of literature and culture explores how the meaning of a text, idea or artefact is produced by way of its relation to the wider historical context in which it is created or experienced. In this context Kamaru not only looks at the society as a social mirror but in addition as a text from which he draws his themes to infuse his songs with new genius in terms of artistic creativity.

The Marxist ideologies in Kamaru’s political songs put him at loggerheads with different goverments of the day during Jomo Kenytta’s and Moi’s era. At, one point, he almost found himself behind bars when he was asked to explain the content in songs such as Cunga marima. In this song the persona issues serious warning to an unmentioned person. The persona tells the person to take care of the way he is treading, there are holes he’s likely to fall into on the road he is treading. This song has double meanings but clever Kamaru got away with it because he stack to the connotative meaning. The same war publication of A Man of The People and the coincidence of the break of the Biafran war almost put Chinua Achebe at crossroads with the Nigerian government, Kamaru’s songs have at some point in his singing career made him face the wrath of political despotism. This political commitment to criticize bad governance is witnessed in most of the song's which Kamaru sang in the 70s when political assassination of prominent figures like Tom Mboya, J. M. Kariuki, took place in broad day light. In a song such as Thia ithuuire mumianirii, an antelope hates the person who exposes it, Kamaru warns appropriates the metaphor of an antelope to warn those criticising the government to expedite their mission intelligently failure to which 'the same hyena that ate J. M. Kariuki happens to eat them as well.

We can therefore observe that while Ngugi wa Thiongo criticized the same political ills in works such as Petals of Blood, and Oginga Odinga not yet Uhuru, Kamaru used song as a literary genre to pass the same messages to the Kenyan society. Kamaru's rich application of irony and satire can therefore qualify him as a master of Literature who has refined his art to bite hard without hurting. This can therefore qualify him as a conscious bard who raises to the occasion to save his society from political calamity. The same way good literature foretells what is likely to come even before it has been experienced, Joseph Kamaru political songs of the 70’s and 80’s resonated with the political climate of the day and he foretell the coming of democracy in his songs long before multiparty era. Kamaru foretold the breakup of fore presidend Moi and his then vice president Kibaki the former vice president even before it happened. As Ngugi wa Thiong’o once observed that a writer responds with his total personality to a social environment which changes all the time being a sensitive needle the writer registers with varying degrees of accuracy and success, the conflicts and tensions in his changing society, Kamaru has used the music scene and the power of the microphone to shape new ways of thinking and to forge freedom of thought and expression the same way Ngugi wa Thiong’o among other writers like Achebe and Wole

Soyinka have done using the barrel of the pen. Other artists such as D. O. Misiani, John De Mathew and Muigai wa Njoroge have done the same following Kamaru’s footsteps and their commitment to producing music that addresses social evils has not spared them the wrath of the law as well. The political consciousness that marks songs of Joseph Kamaru has caught the attention of many because of the artistic manner in which he employs metaphor, and tonal nuances to criticize social evil. As Kimani Njogu observes in Songs and Politics in Eastern Africa, the post-colonial government sponsored choirs which composed music to perpetuate hegemonic normalcy and maintain the socio-political status quo. Joseph Kamaru and D.O. Misiani, however questioned this interpretation of patriotism. Kamaru and Misiani instead align themselves with the needs of ordinary people. This did not auger well with Jomo Kenyatta and President Moi during their respective tenure as presidents. At one time Joseph Kamaru’s songs were banned from being played in public places. This is because in all he’s political songs Kamaru employs social political tonal structures that criticize leadership inefficacies that define practices of power of the previous regimes. This in effect, generates emancipative nuances that forge a course for political consciousness on the part of the masses.

In addition to making political statements in his songs, Kamaru can be said to be a social commentator. This is because he has also sang on various social themes such as love, marriage, hard work to mention a few. In songs such as Ndari ya Mwarimu Kamaru critics how those in higher positions takes use their power to exploit the weak in society. Using the imagery of a teacher who passes a female student whom he has been exploiting sexually, Kamaru frown upon social immorality in places of work and in society in general. The persona in this asks the girl, ndari ya mwarimu (teacher’s girlfriend) every time you are number one…what will you do when the main exam comes? While in class I’ll call you teacher but once we get to your house I’ll call you sweetheart…this invocation of an irony is intended to ridicule both the teacher and the girl for their indulgence in immoral acts. The song in this case ceases from just existing as a mere tool for entertainment. Instead the songs becomes a social tool for moral stock taking.

The song in this context transcends beyond its perception as a music or literary genre and in addition it qualifies as a philosophical practice with which people reexamine how they constiture their being. This is a philosophical position which Michel Foucault has examined in Ethics Subjectivity and Truth“The Ethics of the Concern for the Self as a Practice of Freedom”. In his songs Kamaru, guides and counsel both the young and the old. In the song, andu a madaraka, for instance, he warns the young energetic men who acquire jobs in the city from falling victims of women in the city who smile at these young men and finally use sex as a bait to exploit the young men. Kamaru puts it clearly in black and white, 'if you happen to see a smile, just remember, she's smiling at your money not you as a person.

The oral nuances that Kamaru employs as a singing technique transcends the message beyond mere statement. This is because he's appropriation of oral speech techniques creates a sense of immediacy with which the listener is cajoled to treat the message. As a feature of moral transcendence we can thus observe that Joseph Kamaru’s like all great works of literature serve to improve the society by criticizing social rottenness on the one hand and praising the good as evidenced in his songs in praise of Mau Mau heroes such as Dedan Kimathi.

The consciencetizing discourse that marks Joseph Kamaru’s songs therefore, deserves further inquiry because it resonates with the changing time. As Joyce Nyairo observed once institutional memory is, in fact, the cornerstone of real development. Thematic Concerns in songs of Joseph Kamaru, draw cognisance to this fact. This is because Kamaru bases his songs on different issues that affect social stability, and cohesion which if ignored can send the country to the gutters. Upon close examination, Kamaru’s Ideological perspective as evidenced in the aesthetic practices that define his songs draws from Marxism political standpoint, anthropological reading of Kenyan society, mythocriticism practices of constituting meaning that is hybridized with Christianity values. It can therefore be coincluded that Joseph Kamaru songs as literary discourses capture the listener mind by invoking artistic ways in which he invites the listener to interpret the world of reality.